All around the world, there are tens of thousands of Passion-themed blog posts have been published this week, some showing more profound insight than others, but nearly all of them written from hearts and minds wanting to honor Jesus’ unthinkable suffering for our sins. I wish I could write one too, but…

It’s not that I have nothing to say. After 48 years in ministry, I doubtless do have insights worth sharing. Yet, right now, for some reason, they seem worth less—worthless—rather than worth more. I suppose the easiest way to explain is to quote the late Corrie ten Boom:

“The more I get to know God, the less I understand Him, but the more I trust Him.”

I was privileged to meet and host Corrie ten Boom a couple of years before she passed away at age 91. It didn’t take long to see that there was no pretense about her. When this stoop-shouldered, tiny giant of the faith said something that wowed us all, she wasn’t attempting to be profound; she was just being honest. Likewise, I just want to write something honest here.

I saw Mel Gibson’s “The Passion of the Christ” on its opening day, 1994, at an IMAX theater in Tulsa, Oklahoma, and my most vivid memory of the experience is what happened after the movie had finished. The credits started to roll, but no one rose to leave. Nobody talked or even made a sound, save for some stifled sniffles of emotion. It was only as the screen finally went blank and the lights came up that we started to file out and head to the parking lot. Even outside, as people headed in all directions towards their cars and SUVs, there was silence.

What could we say? Like Ms. ten Boom, now we knew more, so we understood less. And really, the only people with a lot to say seemed to be those who knew nothing but thought they understood. Hence, effete movie critics, Hollywood’s self-appointed moralists and the Professionally Offended class all pronounced the film anti-semitic, which is like accusing the reporter who covered the Hindenburg airship explosion of being an arsonist.

I bought the movie as soon as it was released on DVD, primarily because I wanted to show it someday to my daughter, who was only two when it debuted. And so the disc sat shrink-wrapped on a shelf for a dozen or so years, until this week when our family sat down and watched it together.

The main reason we waited until now is that she is what most folks would call a “young” fifteen. Naïve. Innocent. Sheltered. Sheltered is an interesting word to me, because it should be a compliment, but most people employ it as a slight insult. The truth is, she’s a young fifteen by today’s standards only because her generation has been largely left unsheltered, from chatroom to schoolroom, and exposed to tons of junk that render them an old fifteen by traditional standards.

Yep, she’s sheltered, and with the exception of a radio station we recently banished from her clock radio, as well as the occasional damn or hell she might hear from the likes of Basil Fawlty or George C. Scott’s Patton, her mind has remained relatively unsoiled. (Losing screen privileges for a week has also worked great on occasion as a spot remover.)

We finally watched The Passion together because we want to make sure our daughter truly owns her faith in Jesus, so that it’s based on more than a prayer she repeated as a child, or because she wants to please her parents or fit in at church. We wanted to get a glimpse of what goes on in the deeper recesses of the mind and heart of a girl whose perpetually sunny disposition threatens to keep her in the shallow end of life.

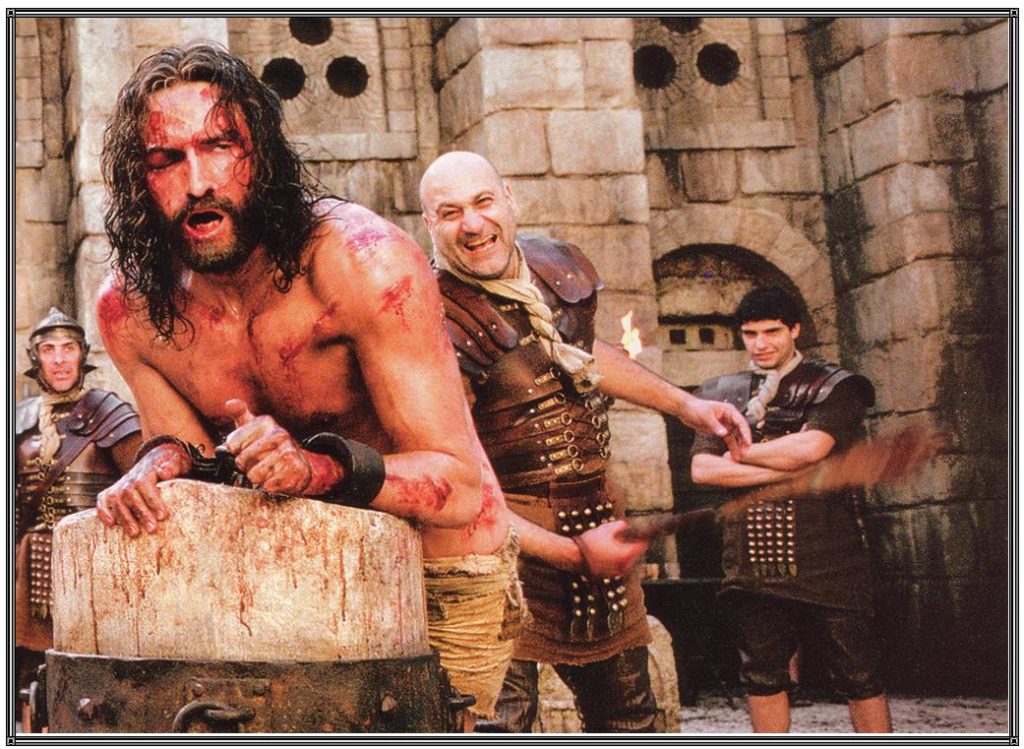

It’s not an easy movie to watch, especially when the scourging of Jesus goes on and on…and on. She looked away more than once, but I reminded her that it’s time now to watch and see, and that Jesus didn’t turn away so neither can we. And so she watched.

Was there a payoff? Did she shed tears or ask us to pray? I would have been happy with either, of course, but she did neither. (Besides, I’d have had a hard time praying anything appropriate.) Instead, she was silent. Just like I was —like we all were—at the theater in 2004. She was silent because now she knew more, but understood less.

I’m fine with that.